Slyght Of Hand

Slyght Of Hand Slyght Of Hand

Slyght Of Hand

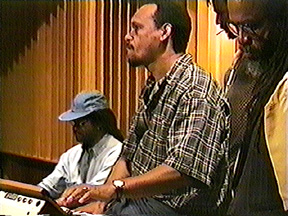

It's a typical evening at the Mixing Lab studio in Kingston.

The large and comfortably secure chamber of the city's most famous

modern recording facility seems a world away from the dark city

streets outside. A television monitor on a wall spews out a continuous

stream of mindless images as an engineer sits over an array of

fader bars at the main mixing board.

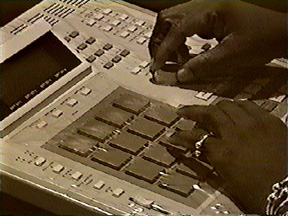

At the back of the room, entrepreneur and production master Sly

Dunbar sits intently behind an Akai 3000 drum machine, wheeling

every control, honing every meter, listening for the perfect sound.

Dunbar's casual appearance (denim clad with sunglasses and a roundtop

baseball cap) belies his significance to reggae music.

Nearby, singer Pam Hall carefully reads over her lyric sheet.

Dunbar sets the opening measures of the Heptones' version of Curtis

Mayfield's "Choice Of Color" in a continuous loop. Over

the classic Studio One rhythm, thundering bass and a keyboard

lead erupt from the hands of Robbie Lyn. Sly descends with a modern

drum loop patterning the original, and Lloyd "Gitsy"

Willis sweeps over it all with tougher than tough rhythm guitar.

Although Lowell "Sly" Dunbar is primarily known as

the drumming half of the rhythm team of 'Sly and Robbie,' he currently

spends all of his time as the principal operator of the Mixing

Lab and associated Taxi label,

co-owned by him and partner/bassist Robbie Shakespeare. Since

being launched into international stardom with Black Uhuru in

the early 1980s, Dunbar has devoted his time to developing reggae

music from the producer's chair. Dunbar is soft-spoken and sincere

as he sits in a modest office at the Mixing Lab to discuss his

work and career.

"I look at [dancehall] as part of the lowest form of music,"

he says, explaining his approach to legitimizing dancehall as

a music with longevity. "Rock steady I think is the best

form [of music], cause we have songs. So we can do the same thing

for dancehall [if] we just work on it, cause rock steady came

to that level. People like Boris (Boris Gardiner -- rock steady

session bass player) and all those people they work on it and

bring it to that level. So we could take dancehall and bring it

to that level, too. That is what we are trying to achieve. And

I think it can work [if] you get the singers into it. Sly explains

that the work of Chaka Demus and Pliers, who hit in 1993 with

"Murder She Wrote," was an important stage in the development

he is seeking. Since the track involved a singer as well as a

deejay, it broke with the trends of the time and became an international

hit. "I think people want to listen to a record that last

forever," says Dunbar. "Some dancehall is a one hit

thing and it's over. But I want to take dancehall and [make] it

last forever just like today you pick up and play 'Murder She

Wrote' and it's like, yea!"

The primary obstacle to Sly's goal lies in the nature of the international

record market. He feels there are too many different varieties

of music to combine to make one cohesive dancehall reggae album.

"If you were working [in America] with an artist, you do

some country and western, some rock and roll or R&B, you [don't]

mix it. With us in Jamaica, you have to make reggae, and there

is so many different version of reggae. You have reggae which

is one drop, you have the dancehall sound, you have lovers rock

style. And then you have like Chaka Demus with a kind of ska feel

that you have to do [and] hip-hop. So you have like five different

kind of music on one album for you to go into the international

market. If you do a straight up reggae album, some of the record

companies can't sell it, because hip-hop has gotten so big. You

have to dilute the reggae with the hip-hop for it to go into the

channel. So this is the problem we are faced with now."

Modern production trends have caused Sly to program more rhythms,

but he still plays a drum kit from time to time, depending on

the needs of a given producer. "What is lacking in Jamaican

music now, you're not getting the real soul of Jamaican records

as you used to get. You can't tell when every record sound the

same way. And the way you would listen to a drummer and say, 'this

fill is wicked,' you don't hear that no more. We try not to loose

the regular live session sound." Sly is also concerned about

the effect of programmed production on the ability of young drummers

in a live setting. "The thing about reggae live - it haven't

got any feel [anymore]. The drummer what they using haven't got

a feel to know when to jerk this rhythm some more; they don't

know how to push high hat - jerk it and make it real. Sometime

you listen to it, and it feel like this (he makes a weary droning

sound). If you're playing a one drop, you [have to] make it sound

solid. When they go into a studio they can get it [to] sound perfect,

but when they do a live concert and listen back to a cassette,

I don't know. With machine technology I don't think it giving

them a chance." While the electronic revolution has changed

the playing field, Sly says reggae is still growing and evolving.

He says that comparing reggae to rock and roll or reggae to R&B

over a given period shows relatively how much reggae has changed.

"If you go back and listen from the first time you heard

reggae until know, it's so much changes it has gone through you

would believe that it's the only kind of music that keep adding

new color to it every time. It just keep on growing."

Dunbar likes to produce every style from the sparsest, most hardcore

dancehall rhythms to mellower, one drop roots and everything in

between, but his primary focus is finding great singers and songwriters

to use his rhythm tracks. Among the artists who commonly record

for the Taxi label are Ambelique, Anthony Red Rose, Chaka Demus,

Ini Kamoze, Red Dragon, Yami Bolo, Bounty Killer, Michael Rose

and Pam Hall. In reality, almost any successful singer in Jamaica

has voiced at the Mixing Lab at one time or another.

Sly is continually searching for the next direction for reggae.

He gives the example of a version of Marcia Griffiths' "Truly,"

originally recorded for Coxson Dodd's Studio One in the late 60s

and rerecorded by Taxi several years ago. Sly combined a dancehall

drum pattern without a bassline (in the same style as the 'Bogle'

rhythm used on "Murder She Wrote") and a sustained chord

(like one would find in a soul tune) to complement her vocal.

He felt the experiment was ahead of its time musically, even though

it didn't turn out to be a hit.

Sly encourages his engineers to experiment and take chances as

well. He elaborates on a number of current production trends,

some of which may sound bizarre. "What's going to happen

now is merging the dancehall with R&B and dancehall with like

country western - just to make it different. Some of the engineers

are trying to do so many mixes, and [they] start merging a dancehall

beat with a soul type of keyboard, and it's working. So we gonna

take it now and experiment on it and try and get some singers

to come and write some songs to it. It would be an element of

the hip-hop beat and parts of the dancehall beat instead of changing

the dancehall beat to hip-hop beat. And we're going into samba,

the Brazil kind of rhythm - the salsa. We're going to incorporate

the whole of that. You might not sell a million copy or even ten-thousand

copies, but if people see what you're trying to do, people probably

appreciate the musicians trying to do something that sounds good.

That's what we are really all about, putting little changes into

the music, keep on updating."

Sly Dunbar's achievements as a producer are enough to earn him

a permanent place in reggae history, but his contribution to reggae

percussion is equally remarkable and influential. His youth in

the Waterhouse district of Kingston (where he was born in the

early 1950s) and his passion for music were the catalysts for

his career. He laughingly remembers taking his lunch breaks from

school and spending all his lunch money "punching" Studio

One records on a local jukebox. He also fondly conjures up memories

of watching Jamaica Bandstand and seeing the original Skatalites

in all their glory.

"I was really a Studio One fanatic - like everything I owned.

Coxson greatest one I ever known. I used to sit up and listen

to all his things. Jackie Mittoo and Lloyd Knibbs were the ones

who really inspire me, because when me listen to Studio One records,

I listen to the way Jackie play piano or Lloyd Knibbs play drums.

When you see them live, you could see the soul. I'd say, man!

wicked! Wicked! After that, me really get interested, cause it

was like all my life, wherever you were, like in Waterhouse there

was so many sounds, King Tubby's - music every day, every day,

twenty-four hours just keep on playing."

Sly started drumming for organist Ansel Collins at age fifteen.

His first record was a Collins' production with the Upsetters

called "Night Doctor." He then played on the Dave and

Ansel Collins record "Double Barrel," which became a

hit in Jamaica. "[Ansel Collins] was the one who really guide

me on the instrument, cause he used to play drums. So when he

need to do a session, I would be his personal drummer. He [would]

do a floor show sometime, and he would teach me how to play for

a floor show, cause I didn't have the experience." Sly also

gained experience playing with Tommy McCook and The Supersonics

and then with Ansel Collins and Lloyd Parks in Skin Flesh and

Bones. The latter outfit worked at Dickie Wong's Tit For Tat Club

on Red Hills Road in Kingston in the early 70s, becoming known

for an early soul inflected flavor of reggae.

"A lot of people don't know that most of the musicians in

Jamaica, we grew up playing more R&B in clubs than reggae.

I remember playing a typical dance, we play for an hour, and in

the hour you could play like six reggae songs versus the rest

had to be soul [or] R&B. So when we start making crossover,

it's not that we were trying to crossover, but we just think of

recording some funk."

It was during this time that Sly met Jo Jo Hoo Kim of Channel

One Studios. Jo Jo gave Sly some work in his session band which

became known as The Revolutionaries. It was a good choice on Hoo

Kim's part, because it led to Sly's first major rhythmic innovation.

Late in 1974 into early 1975, the Diamonds scored a number one

with "Right Time," thanks to the revolutionary drumming

of Dunbar, who made a rhythmic alteration which subsequently became

characteristic of the "rockers" sound. "That was

the turning point for rockers style. It was the first time the

drum was being played in that kind of pattern," explains

Dunbar, referring to the rhythm played on the rim of the snare

drum. "The first time it came out a lot of people didn't

think I was playing, they thought it was some effect from the

board. Every song we make [at Channel One], we used to cut a dub

to see if the drum sound was alright . . . We wanted the highhat

to be just like Motown. We try and try to get it to sound like

that. When you listen to the Channel One sound you can hear the

drum was upfront in the music."

By 1976, the rockers sound dominated the scene, dub albums were

selling by the cartload, and Sly Dunbar, firmly established at

Channel One, was as well respected in Kingston studios as top

sessioniers Santa Davis, Leroy "Horsemouth" Wallace,

Mikey "Boo" Richards, and Carlton Barrett. Sly's bass

partners in the Revolutionaries were Lloyd Parks, Ranchie MacLean,

and Aston Barrett's youthful protege Robbie Shakespeare. At Channel

One, Sly also did occasional work for Bunny "Striker"

Lee. These sessions were always credited to the Aggrovators and

subsequently mixed at King Tubby's Studio -- becoming immortalized

in the dub tradition. Sly had in fact became so popular from the

mid to late seventies that by some estimates (including his own),

he actually played on a majority of the tracks recorded in Jamaica.

Virgin Frontline went so far as to release two Sly Dunbar albums

-- Sly Wicked and Slick and Simple Sly Man. By the

end of the decade, the Revolutionaries were working at Treasure

Isle Studio with Sonia Pottinger (see the classic Culture albums

of the period), and Sly was also spending some time at Joe Gibbs'

Studio with The Professionals.

Dunbar made two significant career choices in the mid-seventies.

The first was to solidify his rhythmic partnership and close association

with Robbie Shakespeare. The other was eventually focusing his

production attention on an old Waterhouse friend and singer named

Michael Rose. Sly actually began producing Michael Rose and his

brother Joseph as early as the mid-70s. Joseph Rose died in a

car crash in 1974, and the younger brother became more intent

on a musical career as a result. In 1977, the original line-up

of Black Uhuru (Garth Dennis, Don Carlos, and Duckie Simpson)

separated and Duckie Simpson joined forces with Rose and Jays'

singer Errol Nelson. That incarnation of Black Uhuru was produced

by Prince Jammy on the Love Crisis album with Santa Davis

playing drums on most of the cuts (while Sly and Robbie were on

tour with Peter Tosh).

In 1978, Puma Jones joined Black Uhuru in place of Errol Nelson

and the classic line-up had materialized. With Sly and Robbie

producing for their new Taxi label (Michael Rose had actually

been its first artist and founder), Black Uhuru recorded "Shine

Eye Gal," "Plastic Smile," "Guess Who's Coming

To Dinner," "Abortion" and "General Penetentiary"

-- all of which became hits in Jamaica in 1979. Those cuts and

several others were collected on the Taxi and D-Roy labels as

Showcase. The album was picked up by Virgin Frontline for

European distribution, putting Black Uhuru on an international

trajectory. The Dynamic Duo then produced Sensimilla, which

was released by Island Records in 1980. The album is often considered

among reggae's all-time greatest studio work. Over the next three

years, Island would release four Taxi produced Black Uhuru albums

- Red, Tear It Up, Chill Out, The Dub

Factor, and Anthem. The group was at the top of the

international reggae scene when Michael Rose left to become a

farmer in 1985. Though Black Uhuru continued under the leadership

of singer Junior Reid and Duckie Simpson, it will always be ultimately

considered the principle creative product of Michael Rose, Sly

Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare.

Sly explains that the ultra-progressive sound of vintage Black

Uhuru came from translating his observations of the three singers

into music. "It was just looking at the artist and just playing.

If you're around people and you see what they need, you just get

out that music. Like sometime you're seeing people moving. We

didn't know what it was, we [were] just playing what we felt.

We didn't know what was going to happen. We just go for it."

The Sly and Robbie/Black Uhuru sound became known in Jamaica as

the "cutting edge," but Rolling Stones guitarist Keith

Richards' appearance on "Shine Eye Gal" revealed the

group's early rock interests. "If you listen to the drumming

in Black Uhuru, and if you go back and listen to some of the reggae

[of the period], it's not the same thing -- it's different,"

says Dunbar. "I'm playing R&B or a heavy metal pattern

kind of drumming. I wasn't playing the one drop. So what I did

to the drum was give it more power . . . really open the snare

and really bang on it, so this is where the whole 'cutting edge'

come from . . . That's what helped it to break [internationally]

faster, cause people could really relate to the beat when they

heard it."

The success of Black Uhuru obviously owes a debt to the rhythmic

styling and direction of Sly and Robbie, and Sly doesn't hesitate

when asked about defining moments of creativity in his playing

with the group. "'The World Is Africa.' It was supposed to

be like a four bar [bridge]. When you're playing live everybody

can look at everybody and they look at me to give them the roll.

So me pick up and continue playing for another four bars and it

really swing. Every reggae drummer is like four bars [and] solo.

Me like 'no mon, get creative.' So it would be like a fever kind

of groove."

Sly attributes his desire to break new ground to the sheer amount

of time he spent working on reggae rhythm tracks. "If you're

a drummer, and you come in every day and play kick . . . drop.

And you play that for a year, don't tell me the next year you

want to play the same thing. You want to improvise and make it

better. You always stand a chance to play something creative.

[When] you deal with beats, you realize early on that the drum

is where the whole thing is, cause when the drum is there, everything

will lay around it."

Michael Rose, who has worked with Sly for well over twenty years

on some of reggae's greatest tracks, unreservedly calls Sly a

genius. "Sly come a long long way and up to now he still

holds it. Genius, man -- genius at work. Him know when fe change

the sound, cause when him change the sound, everything change,

[and] when the sound change, no matter what, he is always there."

Thanks to Ernie Smith for the trip to

the Mixing Lab and the introduction to Sly Dunbar. For more reading

on Sly Dunbar, look for Ray Hurford's informative article published

in More Axe, Black Star, 1987.

The full transcript of my interviews with Sly Dunbar and Michael

Rose appear in 400 Years issue

three.

Copyright 1996 Carter Van Pelt