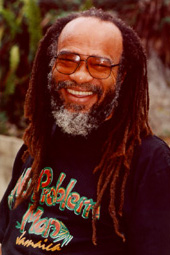

Thank You, Mister Music

by Carter Van Pelt

photo by Horseman

"Thank you Daddy for my first guitar,

Without that one I would have never come this far.

Thank you Mommy for being so cool,

When you let me take that guitar to school."

-- Ernie Smith, from "Mr. Music"

The city lights of Kingston glimmer in a panorama from the edge of the Blue

Mountains in the East down to Hunt's Bay and resume in the distance at Portmore.

The dark void of Kingston Harbor is delineated by the lights on the Palisadoes

in the Southern distance, ending eerily at Port Royal.

This is the vista from singer Ernie Smith's balcony in Red Hills. It was

from this perch one evening in February 1996 that I was indulged for nearly

two and a half hours in one of the most interesting career retrospectives

I have ever heard.

While Glenroy Anthony Smith is similar in many respects to the wealth of

talent that has come and gone through the walls of countless Kingston recording

studios, he is a distinctly unique and enduring entity in Jamaican music.

His songs, with the trademark deep baritone vocals, still play frequently

on Jamaican radio. His name still draws smiles of recognition and familiarity

when mentioned to any Jamaican.

"I was born in Kingston. I grew up in a place called Bamboo,"

remembers Ernie. "We all could sing as kids. My daddy played a guitar.

My mother sang in the choir. We'd be driving in the car somewhere, always

singing. My father used to borrow a guitar and bring it home sometimes.

He bought me my own guitar when I was twelve.

"After I left school I tried to find work and went through jobs. About

five years after school I realized that no matter what job I was doing,

I still was playing something, playing in some band or singing somewhere

at night, and I said, 'this must be what I'm supposed to do.' That was the

constant.

"I was very inhibited, very self-concious, very aware of my shortcomings

vocally. After my voice broke, I didn't think I was going to sing again.

I was putting the bands together. We (always) had a vocalist. I'd sing a

song or two that I had written and that was it. When I started recording,

all of that changed."

Young Ernie grew up with the typical variety of influences from American

and Jamaican radio and the sounds of the Jamaican dance. "I liked whatever

I heard on the radio. I liked the local ska that was coming at the time.

I didn't have a focus yet. I was singing country music, Beatles hits.

"I was working at a place called Renolds (of aluminum infamy). I had

a whole day off from work. I came to Kingston and went to a radio station

looking for a job as an announcer. It was over in twenty minutes with the

'don't call us, we'll call you.'

"I didn't want to go back (home) right away. I went down to Federal

(Records). The piano player was in the studio. I didn't have any problem

going through the doors. I didn't have no problem auditioning. They liked

the song ("I Can't Take It"). I told them they could probably

get somebody to sing it, because I went there as a writer. They told me,

'there's a band coming in at 2 o'clock, why don't you stay and record it.'

So that's how it happened! (laughs)

"I (recorded) three songs . . . I did "I Can't Take It,"

"How Bout You," and "Twentieth Century Paces." At the

time I had left (home), and I was working with a band, and that's all I

was doing. My mother came and said I was wasting my time, (so) I got a job

selling life insurance, still playing music at night. I was getting very

busy and the owner of the studio came to me one day and said I need to spend

some more time.

"The long and the short of it is that after those three first songs,

they decided to spend some money on promoting, making a hit. The first three

(songs) were ballads. But it is interesting, 'Bend Down' was like a country

song with a reggae beat, and that was a hit."

After "Bend Down," Ernie had a string of number one hits with

"Ride On Sammy," "One Dream," and "Pitta Patta."

Federal released an album, Greatest Hits with those songs and a selection

of covers.

Despite his chart and recording success, it took the young Ernie some time

to gain confidence in his singing. "Vocally, I went a long time feeling

left out because I couldn't hit the high notes. I couldn't sing as high

as most people. The first song I sang really low was 'Sunday Morning Coming

Down.' It came out really easy."

During this period, Ernie wrote songs for Ken Lazarus and John Jones, but

none would reach the heights of Johnny Nash's version of "I Can't Take

It," retitled "Tears On My Pillow." Ernie recalls, "He

made a million. It was a big hit. When I went to Germany in 1975, everywhere

I went it was on the radio.

"I was getting known for a kind of easy going ballad. I had done 'Bend

Down,' 'Ride On Sammy,' 'One Dream' as reggae songs. I kept saying to my

producer (Richard Khouri at Federal), 'look, I'm not getting across to the

grass roots.' And he kept saying 'look at the sales figures.'"

From 1967 to 1975, Federal released five Ernie Smith albums (includingGreatest

Hits, Pitta Patta, For The Good Times, and Ernie...

Smith That Is). In 1972, he won the prestigious Yamaha songwriting competition

in Japan for "Life Is Just For Living," a free-wheeling song originally

penned for a Red Stripe commercial. In 1973, the Jamaican government honored

him with The Badge Of Honour For Meritorious Service In The Field Of Music.

Among Ernie's catalog of work recorded during this highly prolific period

are well-known tunes "Duppy Gunman," "Key Card," "Mr.

Music," and "Don't Down Me Now."

The political turmoil leading to the 1976 elections in Jamaica (most visibly

manifested in the assassination attempt on Bob Marley), predicted changes

for Ernie Smith as well. "A lot of the people who bought my records

moved from Jamaica in 1976 because of the whole change in political climate.

A state of emergency was declared. A lot of records were banned. I had written

a song called 'The Power And The Glory.' 'As we fight one another for the

power and the glory, the kingdom goes to waste.' Now it said, 'as we. .

.' I never really pointed at anyone, but the government at the time took

it to be an attack. I wasn't really threatened, but I was beginning to feel

insecure, because people were telling me, 'the Prime Minister don't like

that.'"

Amid the tension, Ernie headed for the Northern climate of Toronto, Canada,

where he would stay for the next three years. The period marked a transformation

for the singer, both musically and spiritually. "Something happened

to me in Canada. I experienced something on stage. I did a show at the harbor

front. There were four people singing and four people sitting on the floor

playing drums. The drums trapped me. I don't know how to put it. I found

myself moving on stage like I had never moved. Something broke loose inside

of me. I felt out of control, but I felt in control. I was feeling like

something cool and clean and pure was flowing through me. That night was

an end and a beginning."

Ernie recorded two albums in Canada. To Behold Jah was Ernie's first

album of all original material, which he laments "was terrible technically,

but the music was cookin. Most of the songs on that album were a kind of

a spiritual search." The album that followed, Skareggae, included

covers of popular reggae tunes from the 60s and the 70s.

"While all of this was happening, I was realizing that my family life

was a shambles. With that self-search, it seemed like I passed everything

through my mind again."

In 1981, Ernie moved to Miami to be closer to his wife and children. The

new environment didn't bode well for him, and the coming years would be

difficult. "When I hit Miami, the realization was hitting me that I

really was not in a position to support my children. I didn't have a roof

over my head. All of these things was coming home to me under the influence

of cocaine. I ended up moving home to Ft. Lauderdale (with my family). And

getting bloody irritable." Ernie spent the 1980s dealing not only with

a divorce, but also a cocaine and alcohol habit that stifled his creativity

and tested his faith and his perseverance like nothing before.

Under the advice of a friend, Ernie went to see Cedella Booker (Bob Marley's

mother), whom he'd never met but felt he should consult. "I was troubled.

I needed some kind of something. I called her up, and I don't remember what

I said to her or how I introduced myself. We ended up talking. I went and

visited her, and I always came away feeling so strong. I ended up living

down there for a while -- just trying to help her do some tracks and write

some stuff for her."

In 1987, Ernie's creative juices were stimulated by writer/filmmaker Perry

Henzell (The Harder They Come), who had Ernie pen the songs for his

musical, Marcus Garvey. Though the material was never released on

record, Perry Henzell still feels it was of superlative quality and said

in a separate conversation that he "would big up Ernie Smith anytime

for the work he did on Marcus Garvey."

The events surrounding Hurricane Gilbert in 1988 would call Ernie Smith

back to Jamaica for good. "After the hurricane I saw certain things

that brought me home. I was in a yard and a guy walked in with a branch

of a strawberry tree. Everyone was walking around from yard to yard exchanging

fruits that had fallen and everyone was grinning from ear to ear and talking

about what a big old breeze it was.

"I go back to Ft Lauderdale, and I'm watchin the news over there --

the traditional melee interview. You interview the person in front of the

rubble of their house, and the person is all over in tears. And them talking

to this man . . . him don't have nothing, him lost everything, (but) him

have a big old grin on his face talkin about (how) it blow hard and it knock

off (his house), but 'me give thanks cause me have life!' And I said 'what

am I doing in America? I'm going home.' He brought me home."

After returning to Kingston and getting his own severely damaged house back

together, Ernie would start writing and recording again and put together

a touring band called the New Agenda. The group didn't stay together long

and Ernie has since made his way and built a reputation as a 'One Man Band.'

"For one reason or another I always end up single," he states

with a smile.

For Ernie Smith, songwriting bears different burdens now compared to when

he was obligated to a record contract. "I still struggle with my own

discipline. I still need to just sit down and write. I will hear somebody

say something, and I will hear a lyric. Sometimes I hear stuff coming so

fast I can't get it down. Sometimes I have to plod and work and slug it

out till I get it.

"Music to me is a catalyst -- both between me and myself and me and

the rest of the world. I can sit and see people and imagine where they coming

from and imagine what kind of day they had and reach out to them."

Ernie's most recent release is a largely rerecorded compilation of some

of his best known hits from the 60s and 70s, done with modern styling and

production. The album, Dancehall Ernie Cleans It Up, marks the first

time his work has been released on compact disc.

His future recording plans are focused on getting together an album of country

music p; a music he has loved since his youth. "There was always

country music programs on the radio. I remember the first little song I

wrote in high school -- it was a country feel."

At the core of Ernie Smith is a man who exudes a kindness and generosity

that is hard to mistake. The markings of success have come with pitfalls

and hardships that make a man full and appreciative of true richness in

its every form. One of his daily activities is to provide transportation

for some local schoolchildren who need safe rides home in the afternoon.

He has also sponsored local youths who need money for textbooks.

As he drives along one afternoon in Red Hills and passes some kids on the

side of the road, they begin to smile and jump and start chanting, "Er

NEE! Er NEE!"

His celebrity has never separated him from his community and his folk roots.

Thank You, Mr. Music.

Thanks to Ralph A. Smith for the introduction to Glenroy Anthony (Ernie

Smith) and the whole Jamaica experience. Apologies to Horseman for the improper

attribution on the photo in Reggae Report.

Copyright 1996 Carter Van Pelt

![]()